A talk on India

Given all the chatter about what’s happening to the Indian economy, I thought I’d post the slides and speaking points of a talk I gave to a class of graduate students — a mix of ‘national security and foreign policy suits’ and ‘liberal humanities hippies’ — about a year ago.

Thank you. By way of background: I work as a macroeconomist, and have worked on SA economic stuff now and then. Ground rules: question of clarification throughout, but substantive questions at the end.

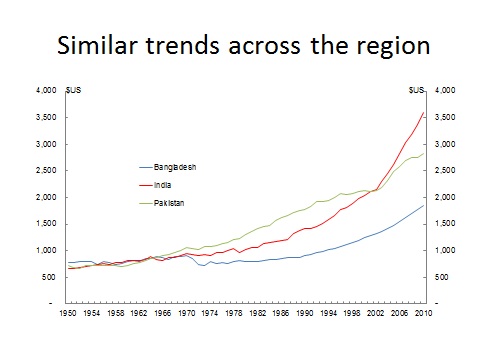

We are supposed to talk about development and PE in SA. Primary focus is on India. And we will use the language and technique of economics. Particularly, GDP per capita.

Not because it’s the most important thing. It is correlated with a lot of important things, and it’s a means to an end about important things. But it’s not the most important thing. Nor is economics or india focus right in and of itself.

But we’ll do so because that’s the easy thing to do. A case of looking under the lamp post. Also a case of elephants and the blind men of India.

Important to keep the elephant parable in mind. Need for multi-disciplinary and critical analysis.

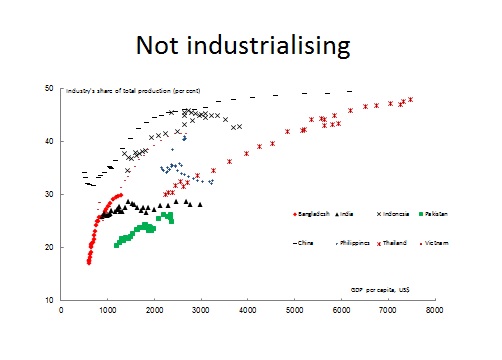

Quick notes about data: sources are GGDC, WB, CEIC Asia; PPP adjusted, internationally comparable.

The is in 4 parts:

Economic History

Kaushik Basu writes about India being a land of present participle — rising, shining, arriving. Let’s look a bit into the past.

A bit, not much — no mention of pre-independence stuff, though in a sense India (like China) is just going back to where it was in great scheme of things, and there is a literature and research agenda out there about ‘why not India’ re: industrialisation, or the effects of the Raj etc.

We’ll not talk about those. instead, we begin with Nehru — destiny refers to the speech.

Basic fact – India (and SA) still very poor, though things are getting better.

At independence, India’s economic thinking was dominated by a suspicion of foreign capital, and the outside world as such. East India Company came to trade, and became the ruler. This left a deep mark in the Indian psyche.

Among the nationalists: Gandhi’s village republics, didn’t really have many takers; domestic organised labor, some communist backed; domestic capitalists supported Congress.

Skepticism about the market was not just an Indian thing in the post-war world. In the west, great depression and the war convinced the intellectual mainstream that capitalism needed govt intervention. Keynesianism. Soviet Union provided a more radical model. And for the poor countries, everyone agreed on the need for the ‘big push’ – govt should provide support to the key sector, and spur growth.

Nehru synthesised these domestic and global ideas. He talked about science and technology being India’s new religion, and dams and steel mills its temples. PC Mahalanobis, a physicist turned statistician, symbolised the Independence generation’s ideals.

India started with good institutions (relative to other countries). Planning Commission.

Importantly, vast part of the economy was never ‘nationalised’. Particularly, agriculture. Key difference from the eastern bloc countries, and with important consequences.

Planning doesn’t work because of information and incentive problems. Govt cannot know how technology and preference changes. When the price mechanism doesn’t work, there is rationing. The system breeds corruption. Rajaji’s critique.

India faced a series of political and economic crises in the 1960s and early 1970s. Wars with China and Pakistan. Congress leadership tussle post-Nehru. Severe drought and crop failure. Rise of Indira and populism – garibi hatao. Bank nationalisation.

Then early 1970s oil shock.

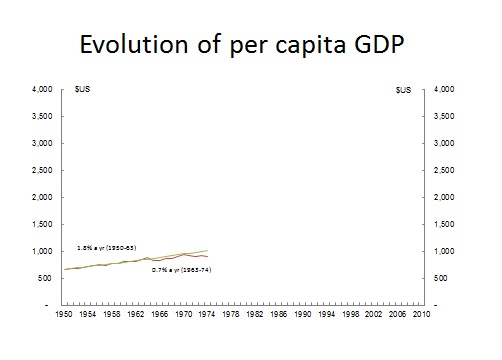

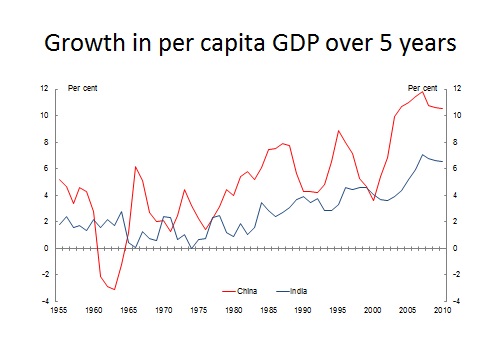

All these led to the ‘Hindu rate of growth’ (Raj Krishna).

3-3.5% a yr GDP. 2-2.5% a yr population. 0.5-1.5% per capita income.

Note the slowdown in the 1960s.

When and how did the Indian economy turn around?

The simple story of stagnation until 1991, crisis, heroic budget, epic reforms, and happily ever after.

But economists are a multi-limbed mob (Truman wanted a one-handed economist).

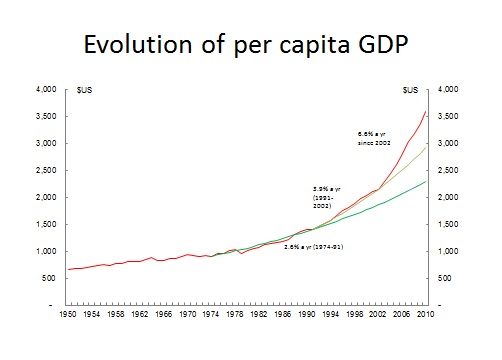

And the story is more complicated. We see three separate accelerations. Late 1970s. 1990s. 2000s.

Even during the hindu rate years, there were two notable things. First, green revolution. Self sufficiency in grains. Recall: india didn’t have collectivisation. Second, while banks were nationalised out of populism, it did have a positive side effect – higher domestic savings è eventually translate into investment.

After returning to power in 1980, Indira tilted towards business. Rajiv also business friendly. But these reforms were ad hoc and had little overall framework.

The well known story of 1991.

The 2000s — the greatest decade.

Sustainable?

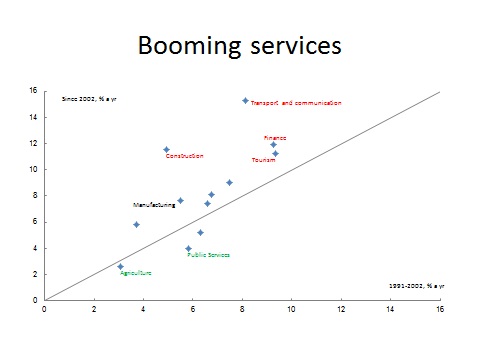

What boomed?

3 modern services.

Also construction – infrastructure building.

Manufacturing is middling.

Agri and public lags behind.

Largely the same story in Pakistan and Bangladesh.

To note:

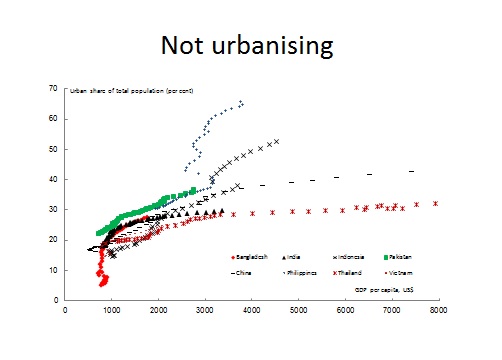

Typically, growth is accompanied by industrialisation.

Typically, growth is accompanied by industrialisation.

Surplus labour goes to factories, trickle down. India not industrialising. Whether service sector led growth can create broad-based prosperity is a subject of exciting research.

Similar to industrialising is urbanising. India is less urban than others.

Why? And what are the implications? Consequences for welfare?

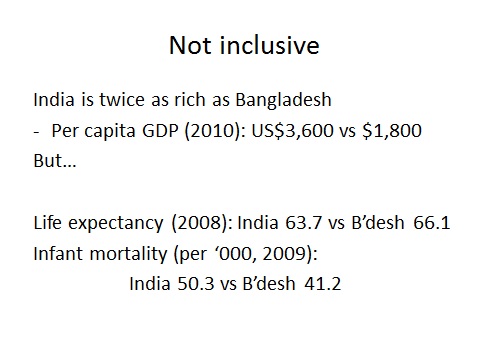

Recall GDP is means to an end. Money can’t buy you love, or happiness. But money should buy you stuff.

Turns out that growth hasn’t trickled down as much as it should have.

Political economy

Why?

I’ll sketch some very tentative research agendas.

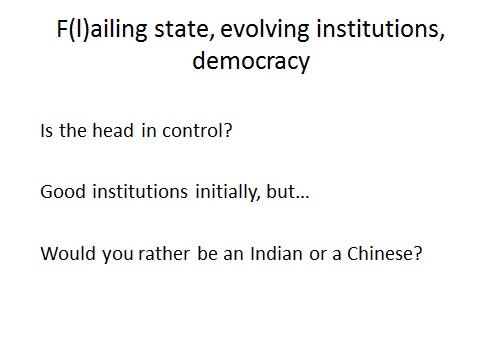

Weak vs strong state. Lant Pritchett’s flailing state.

Weak vs strong state. Lant Pritchett’s flailing state.

India started out with good institutions that were weakened during the licence raj years. In the post-reform era they seem to have weakened further.

Why? And how should we think about these?

Some people talk about China’s strong state, or the Chinese model of benevolent authoritarianism.

Well, here is one way to think about it.

Independent India didn’t have the Great Leap or Cultural Revolution.

Weak democracies can’t screw up too badly!

Two possible paths.

The area of darkness – Naipaul, Adiga.

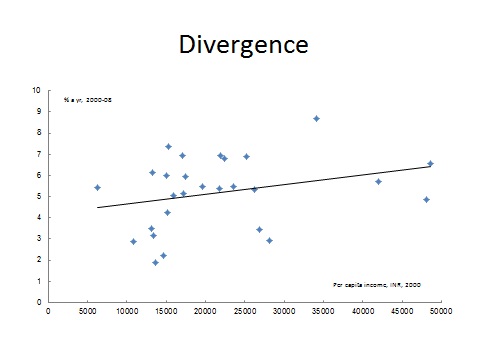

Neoclassical theory says that if all else equal, poor states should catch up.

Theory fails.

Why?

Convergence is the ultimate policy challenge for Nehru’s Noble Mansion.

Here goes my comments –

1. Wonderful read, you captured a brief of India’s economic history. Nice passage through time …

2. You can upload the slides into slideshare.net or google docs and make it public. It’s easier to read that way.

More coming …

Will do.

“India started with good institutions (relative to other countries)”

– well, I don’t see any reason to comment that. India took the idea of Planning Commission from Soviet mentors that were also replicated in Korean, Malayasian, Chinese and Pakistani system. There are no means I could conclude that Indian planning commission was superior to either of their counterparts.

“1971 lowered BD starting point”

– Yes but the gap between India and Bangladesh was created in the boom decade only. You can look at 2000-2010 growth rates. Its the same in Pakistan.

Now coming to the inclusiveness, you have pointed out social indicators of India and Bangladesh but the indicators of public health is largely dependent on success rate of public campaign, which is always better in homogeneous countries rather than heterogeneous ones. This is a structural problem in India but I don’t see any reason we should criticize the state or the institutions for this. I am pretty sure Bangladesh will expand this gap continuously unless some catastrophic events strikes it. The same way – access to drinking water and sanitation would much less problem of Bangladesh because of Geographic reasons (per capita availability of water is 3 times that of India).

I see Poland, which has less than half of per-capita income of USA, has higher life expectancy and same infant mortality rate of that of USA. Is that an issue for USA? The task upfront is much tougher for USA than that of Poland.

Slow movers need not be less efficient if he’s carrying larger weight.

Coming to the divergence, I read an article in The Hindu which says that after 2000, India observed convergence.

http://www.thehindubusinessline.com/opinion/columns/c-p-chandrasekhar/article3418631.ece

http://articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com/2012-06-06/news/32078998_1_poor-states-backward-states-growth-data

I will try to collect more data on it.

“Would you rather be an Indian or Chinese”

– Oh, not Chinese or Cuban, where I can’t read your blogs :), China has banned wordpress blogs along with Google search … 🙂

I think the question could be broken down. Would you rather be poor in India or China? Would you rather be middle class in India or China? Would you rather be rich … would you rather be creative … would you rather be religious … would you rather be a minority …

Perhaps you’ll get different answers across the range of questions.

Indeed.

Diganta, let me cover three issues — institutions, convergence, social progress — together.

In economics, institutions refer to not just individual government agencies or private firms, but the whole set of written and unwritten ‘rules of the game’ that governs economic and political life. There is a huge literature on this. Daron Acemoglu and Francis Fukuyama are the two currently active big names in the field. At the risk of overtly simplifying, better institutions are those that minimise transaction costs (it’s a lot more complicated, but for us this will do). If a firm knows where it stands in terms of taxes (or bribes), court decisions or social customs, then its investment decisions will be easier to make.

Compared to other newly independent countries, India had better institutions in this sense. Its bureaucracy or courts or public ethics provided for lower transaction costs. Arvind Subramanian has written on this. Planning Commission is a specific example.

On convergence, I don’t think these articles are saying there was convergence in the 2000s. It’s saying poor states were not falling as much behind in the 2000s as they were earlier, and some mid-ranking states converged. Also, one of the article uses net domestic product, while the conceptually correct and commonly used measure is gross domestic product.

You make a correct observation that heterogeneity makes it harder for social inclusiveness. But that doesn’t make the issue less important. Economic growth or fiscal sustainability are means to an end, the end being better living standards. All else being equal, perhaps India needs to be richer than Bangladesh to deliver same standard of living. But if so, then would a corollary be that it’s better to break India up? But then again, would things have been better if there were half a dozen states engaged in an arms race?

Also, social services are state responsibilities, right? And individual states are not more diverse than Bangladesh, are they? So perhaps it would be better to look at the state dimension of this? Perhaps even though there hasn’t been convergence in GDP, there has been convergence in social issues?

I think Ejaz Ghani has done some work on this. Will look up.

As an aside, average American spends twice as much on health care and has worse results than an average European. If it’s not an issue, it absolutely should be.

Nice answer 🙂 … loved it.

I need to read a few articles on institutions, and I would try to understand this. The court, stock market and other systems are till date better in India than in China. But labor law and bureaucratic tapes are worse in India. Sometimes I feel bureaucratic processes in US is even worse but they have automated a lot of those and there’s more transparency in the process (+ the obvious, people on average are far more honest). So, they escape the tapes. But if you really measure it in terms of “minimum transaction costs”, they you may probably end up with a conclusion that any autocratic state has better institution than the democratic ones.

I agree that India will have to use more resources to maintain same average standard of living than that of Bangladesh, at least till everyone gets up to a minimal standard and the process becomes self-driven. I am not going into split/united India comparison but over a time period, some of the states failed and the whole number is skewed by those ones. You can see page A123 here, how it stacks up statewise.

Click to access estat1.pdf

And I am still studying convergence. I have seen US States does it quite well, but China and Russia fails on that. How about in Australia? Convergent?

I don’t think ‘any’ autocratic state has better institution — defined as minimising transaction costs — than democratic ones, though certainly some autocracies can have better institutions. Autocracies, even very benign/benevolent ones like Singapore, have one fundamental source of uncertainty — they don’t have a good mechanism of succession / regime change. In addition, they have the ‘bad emperor’ problem — what do you do in an autocracy if the autocrat turns out to be incompetent (never mind whether they are benevolent or not). As a result, even if at any point in time some autocracies seem as if they have great institutions, over a long enough time horizon, democracies do better.

Which, incidentally, is the most important reason to be hopeful about India.

India is also twice as corrupt as Bdesh, based on its mega millions in mass poverty.

In terms of inequality, China > India > Bangladesh. So, as per your concept, the corruption ranking should be reversed 🙂