Corona Budget: the Long View

The public discourse around the budget in Bangladesh is limited to a few days in the middle of June when news outlets parrot the government talking points, and a handful of critics recycle the same arguments — that the budget is unrealistic (if not based on false data) and not pro-poor enough (if not actually enabling the rich to become richer through massive public corruption). Remarkably, hardly anyone ever mentions the medium term macroeconomic policy statement (MTMPS) — the most important document released by the government every June.

I wrote very similar words a decade ago, in the Daily Star Forum. Along with fellow Drishtipat writer Syeed Ahamed who used to pen a piece titled Budget: the good, the bad, and the uncertain, the July issue of the Forum would print the Long View where I would analyse the MTMPS (yes, an ugly acronym if there ever was one — must have been an econocrat who came up with it!).

Much water has flown through our delta over the years since both Drishtipat and the Forum ceased to exist. But a few things remain unchanged: the government still publishes the MTMPS in the Ministry of Finance website; hardly anyone talks about it; and the budget discourse is still same as it was then, albeit done more in Facebook than anywhere else.

The Statement typically begins with a summary of the key budget announcements, before providing a detailed analysis of the macroeconomic projections — how fast the economy is expected to grow, driven by which sectors, and what that means for external balances or inflation, and ending with a fiscal analysis — expenditures, revenues, deficit and its financing, and the dynamics of public debt. Interesting side note: the current Secretary of Finance, Abdur Rouf Taluqder, led the team that put together the country’s first MTMPS in the mid-2000s.

Published in the midst of the most severe economic crisis in over four decades, the importance of this year’s MTMPS is self-evident. The document is internally consistent — that is, the fiscal outlook is consistent with the macroeconomic narrative. Of course, it would be an understatement to say that there is considerable uncertainty around the macroeconomic outlook. The truth is, no one know when and how the world will recover — when and how the pandemic will end, what and how the society will adjust to, and therefore how fast the world economy will grow by when: no one has any answer to these questions.

As such, any quibbling over the numbers in MTMPS is completely besides the point. Much more important is that the Statement has no scenario analysis — what if the world does not evolve the way Mr Taluqder’s talented team expects it to?

This is not a rhetorical question. The Statement is based on the IMF’s World Economic Outlook from April 2020, which projected the world economy to contract by 3% in 2020 on the assumption that the pandemic would end in the first half of the year. Judging that this assumption was no longer tenable, the Fund updated its forecasts in June — the world economy was now projected to contract by 4.9% in 2020. Emerging and Developing Asia, of which Bangladesh is a part, was now expected to contract by 0.8% in 2020, compared with a 1% growth forecast in April, with the downward revision reflecting a worsening pandemic.

The IMF revisions alone might render the MTMPS less-than-credible!

It is regrettable that risks and uncertainties aren’t explored at all in the Statement, as some back of the envelop calculations show that the government could well face some difficult choices in the coming years.

To do such fiscal scenario analysis, we need to estimate how much tax revenue the Government might be able to collect, and this cannot be done without a view about the size of the economy. That is, we need to have a view about the growth in the real GDP — that is, everything that is produced in the economy — as well as inflation — that is, how prices of goods and services change over time.

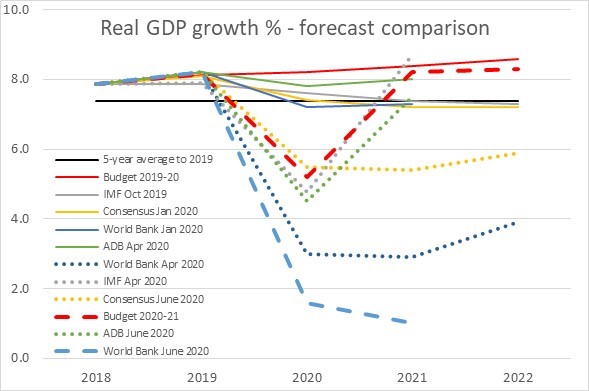

In the 2019-20 Budget, real GDP was forecast to grow by 8.2% in the fiscal year that ended on 30 June. Of course, no one could have known the pandemic in June 2019 when that Budget was published. As the pandemic hit, economic activities were affected by both direct results of various lockdown measures — which were most stringent in Bangladesh during April and May — as well as the indirect effects of global economic slowdown. Reflecting these, in the current Budget, real GDP is expected to have grown by 5.2% in 2019-20. The economy is then projected to stage a sharp rebound, growing by 8.2% in 2020-21 and even faster in the following two years. This is shown by the first chart below (source: CEIC Asia and the Ministry of Finance, years end on 30 June).

To put things in context, the annual average economic growth in the five years ending June 2019 was 7.4%. In the 2019-20 Budget, the economic growth was set to accelerate. While not as rosy as the official forecasts, before the pandemic, the IMF, the World Bank, and the private sector forecasters all expected strong growth to continue into the 2020s. In the chart below, these pre-pandemic forecasts are represented by the thin solid lines. The thicker, dashed / dotted lines represent the post-pandemic forecasts as they evolve.

From the chart, it appears that the strong rebound projected in the MTMPS is in line with what the IMF was projecting in April, and not that dissimilar to what the ADB was projecting even in June. Visually akin to the letter V, these forecasts describe a rapid recovery as the pandemic ends. Applying the labour market dynamics of the past recessions to the current US economy, Robert Hall (Stanford) and Marianna Kudlyak (San Francisco Fed) expect a post-pandemic V-shaped recovery. Andy Haldane (Bank of England) says the UK is on track for a V-shaped recovery. And Jim O’Neill (Chatham House) assesses from high frequency data that a V-shaped recovery is still more likely than not.

But then again, as noted, the IMF forecasts that underpin the Statement have already been revised downward. The IMF revisions for India is particularly instructive. In April, India was expected to grow by 1.9% in 2020. Then came one of most stringent lockdown, at least on paper. Since the lockdown has been lifted, India has been experiencing a particularly virulent outbreak. Arguably, India experienced the economic hardship of the lockdown without public health benefits. In June, the IMF expected the Indian economy to contract by 4.5%.

Could Bangladesh be experiencing something similar?

There is a veritable alphabet soup of potential recovery trajectory. There is the U-shaped path, which similar to V in terms of a rapid rebound, but the trough is lower and longer. Then there is the W-shaped recovery, where an initial rapid recovery is likely to be followed another sharp deterioration in case of a pandemic second wave — this may well be happening in the US.

Finally, there is the L-shaped trajectory, whereby the economy does not actually recover to the pre-pandemic trajectory into the medium term. Essentially, the pandemic lays bare the existing problems in the economy or scars enough sectors in a way such that it continues to grow at a much slower pace even when the pandemic is over. For example, as of June, private sector forecasters (mainly multinational banks) were expecting growth rates of less than 6% into the mid-2020s for Bangladesh.

A much starker, and grimmer, L-shape (or a beginning of the U) is projected by the World Bank — its June forecast is for GDP growth of 1.6% in fiscal year 2019-20, to be followed by a further slowing to 1% growth in 2020-21. That is, according the World Bank, the worst is yet to come.

Again, the point here is not that the MTMPS is too optimistic. The truth is, no one really knows how the economy will evolve because no one really knows how the pandemic will evolve. The point, rather, is that what if the recovery was anything other than V?

The strong recovery being projected in the MTMPS reflects ‘investment in social infrastructure and private sector industry by ongoing reform initiatives and various stimulus programs’. Any analysis of the efficacy of these reforms would require one to have a view about the post-pandemic economy and society. And any stimulus measure would cost money, which brings us back to the question of ‘what if things were harder’?

Specifically, suppose the World Bank’s April growth projections were to materialise — what would be the fiscal impact? To answer that, we would also need to have a view on inflation. With real GDP growth and inflation, we can calculate nominal GDP, which is the broadest measure of the government’s revenue base. A more sophisticated fiscal analysis would require knowing the trajectory of household consumption (to analyse VAT) or the shares of the economy accruing to workers as wages and salaries and to the capitalists as profit (to calculate income taxes). But nominal GDP can yield back of the envelope results that could still provide insights.

As the pandemic hit, oil and other commodity prices collapsed in the world market. All else equal, this augured well for the inflation outlook for commodity importers such as Bangladesh. Against this, however, was unprecedented capital outflow from emerging markets in March and April, when investors fled to the safety of US dollar denominated assets. As a result, currencies of many emerging countries depreciated sharply, creating inflation pressures. Bangladesh was spared the carnage, possibly because the financial market is not globally integrated. Food prices might have spiked, but hasn’t. Taking into account all these factors, inflation is expected to remain stable and subdued at 5-6% range by various forecasters, with the private sector forecasters expecting a dip in 2020 calendar year (next chart).

This then gives us a basis for a scenario analysis. Specifically, we want to analyse the scenario based on the World Bank’s April projections as follows:

The World Bank projections imply that the nominal GDP — that is, the value of all economic activities in a year without adjusting for inflation — would be growing by over 9 a year during 2019-2022. This compares with an annual average growth in nominal GDP of over 15% in the MTMPS. The MTMPS also projects revenue to grow by nearly 20% a year in the same period. This implies an elasticity of revenue to GDP of nearly 1.3 — that is, each 1% rise in nominal GDP is expected to result in a 1.3% increase in revenue. Applying this elasticity to the scenario growth in nominal GDP gives the scenario trajectory of revenue — which is expressed as a share of nominal GDP in the chart below.

Translating this into hard cash — were the scenario of slower growth as par the World Bank projections from April to materialise, this back of the envelope calculation suggests that government revenue would fall short of that projected at the Budget by 488 billion taka in 2020-21 and nearly 495 billion taka in 2021-22. Large numbers like that are meaningless in the abstract. To put them in context, expenditure on pay and allowances of public servants was 534 billion taka in 2018-19.

Of course, there is no suggestion that if the revenue were to fall short as implied by an L-shaped recovery scenario then most government employees would be fired! But if revenues were to fall short, the government will have to make some difficult choices. Should expenditure be cut by similar amount as revenue shortfall? If so, what should be cut — public servants’ salaries, public service jobs, or other expenses such as the annual development budget? Alternatively, should the government try to finance the revenue shortfall by borrowing — if so, from whom? What will be the implications of the higher budget deficit, noting that the deficit is already expected to widen as a result of the pandemic?

These are precisely the kind of question that the MTMPS does not answer.

Comments Off on Corona Budget: the Long View